OPINION: Enrollment into A.P. Classes Should Follow a Prerequisite System

February 13, 2015

Advanced Placement (A.P.) classes are an opportunity to move up, both in one’s intellectual growth and in an official capacity. “It’ll look good on my college applications!!!” sounds familiar, right?

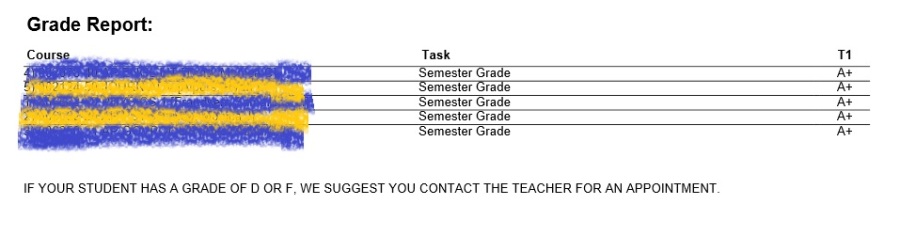

This opportunity is currently open to all students at Lincoln, regardless of their past grades or previous failures in other A.P. classes. Not all students take advantage of Lincoln’s A.P. program– and it actually looks better to both colleges and parents if a student takes home high grades in non-A.P. classes as opposed to a row of D’s or F’s in A.P. But others do make that decision to take A.P.

Among those who take A.P. classes in their junior and senior years, a good number end up being sub-par students who cannot keep up with the workload required to earn a high grade. I cannot generalize and say that this comes purely from a lack of motivation, other priorities, English being a second language, low intelligence, or poor teaching. Multiple factors may contribute to this school’s significant failure rate on A.P. exams.

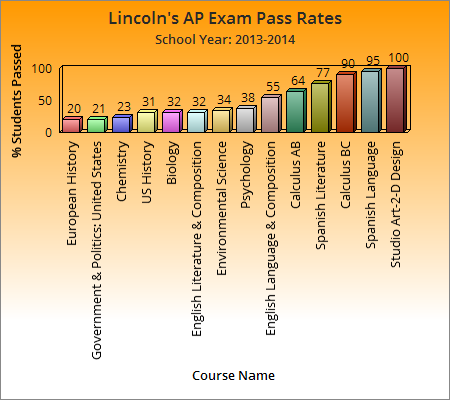

What the Rate of Pass Says About a Class

A.P. social studies courses, especially, have an extremely high volume of students clamoring to be enrolled in them. The A.P. versions of U.S. History and U.S. Government are each taught by several different teachers, because that’s what is necessary to meet student demand. Not a bad thing in itself, but proficient students could probably be consolidated into two or three classes if they were the only ones allowed to take the course in the first place. The poorest pass rates of all belong to European History and U.S. Government, at 20% and 21%, respectively.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are just three class sections of A.P. English Language and Composition for 2014-2015, and three of A.P. Calculus (AB and BC combined). Students in these typically smaller classes tend to perform better on their exams than those taking exams in history or government. More than half passed English Language in 2014, and it is a supermajority that typically passes Calculus every year.

Then there is another outlier against the realm of low scores; Spanish Language has nearly all students passing its exam. Why? I am not calling the Spanish Language exam easy, but let’s just say that I earned a 4 on it, despite my Spanish skills being mediocre. Likewise, Studio Art 2-D Design, which had 100% of students passing and requires a portfolio instead of an exam, cannot be judged on the same playing field as the rest of the A.P. courses.

Far from easy, science courses such as A.P. Chemistry and A.P. Biology have dismal pass rates, with less than one in three students passing, likely because of the complicated math concepts that students are not sufficiently prepared to take on.

The wide gap in pass rates may be a result of classes such as A.P. Calculus BC providing students with a more focused learning environment among a winnowed-down field of peers who truly want to be there. As it is, the subpopulation of students who take three or four or five A.P. courses per year are the ones who know they can handle it and who are passing those courses with lower enrollment, like A.P. Calculus and A.P. English Language. For reasons unknown, A.P. of the social studies variety tends to be the one that hordes of students take as their sole A.P., so the pass rate is bound to be lower.

A Couple of Case Studies

Despite the overwhelming interest in A.P., college-level in high school isn’t for everyone. And kids who just want to sit around and forgo their homework can sometimes even exasperate a teacher who has high standards. Here’s one example:

In my A.P. U.S. Government class last semester, the teacher would go row by row asking students basic content questions from the reading. Often, one person after the next would admit they had no idea of the answer, and the teacher would spend twenty minutes asking twelve or thirteen different people one simple question. This took time away from more complex comprehension activities we could have been doing, and even high-achieving students might have found themselves falling behind come the end of the year. In turn, increasing the rigor of A.P. courses might lead to better scores.

If a student is willing to put in the hard work, he or she will have the best chance of success, earning an A or B semester grade and a passing score on the imminent A.P. Exam in May. This is where there lies a conundrum: students who are not willing to work keep piling on the A.P. courses anyway. Why? Who does it help? They are certainly not helping themselves. The possibility of exempting a general education course and saving money in college is an incentive, but to earn college credit a student actually needs to pass that exam.

One 11th grade student in my acquaintance, who has asked to remain anonymous because he revealed information about his grades, has had a love-hate relationship with Lincoln’s A.P. program.

“I took A.P. Chemistry last year and I got a C in that. I took [an unnamed A.P. class] last semester, and I failed it. I took A.P.U.S.H [U.S. History]– I got a C. I took A.P. Physics and got a C,” he said. He did not pass the Chemistry exam last year, and has yet to take the other exams.

Despite poor results, he keeps taking A.P. because, “they’re fun. The challenge,” while at the same time admitting that “yeah, it definitely hurts [after high school] to fail a class.”

The student reported that he had never run into any problems signing up for A.P. classes, even when he earned below average or failing grades the previous year in non-A.P. coursework.

When asked about what Lincoln could do to raise its pass rates, the student responded, “Some students who sign up for A.P. classes might not be ready and aren’t prepared for the amount of work… I think there should be small prerequisites but you probably shouldn’t stop any kid from taking a class.”

He added, “Maybe they should explain like actually how hard A.P. classes are instead of just saying ‘A.P. is good for you, to go to college.’ Some people sign up thinking it will help them go to college but then they fail the class, and they can’t go to college.”

So What?

Lincoln’s got something going for it: Anyone who wants to succeed academically here definitely has the opportunity to do so. But equality of opportunity does not ensure equality of outcome. There is a self-defeating cycle here that we must take notice of. Students taking classes they are not prepared for does not fix the “opportunity gap” and help them catch up. Rather it makes them fall further behind.

To help students succeed, the school needs to leave more at stake. A system of prerequisites would put the burden of responsibility on students. Past success or failure in a subject area has been proven to indicate future performance (College Readiness for All: The Challenge for Urban High Schools). Therefore, here’s an idea:

Only if you earn a B- or better in English 3/4 can you matriculate into A.P. English. Only if you earn a B+ in Precalculus or a C+ in Honors Precalculus will you have the option to take A.P. Calculus. Only if you earn a B- or pass the exam in A.P. U.S. History can you remain in the A.P. program the following year to take A.P. Government.

The grade thresholds I have laid out here are hypothetical. Lincoln’s administration and Curriculum Council could set the prerequisites that make the most sense to arrive at the best chance for student success. This could include a minimum level of math to be eligible to take a math-heavy science course like A.P. Chemistry or A.P. Physics.

We cannot pander to the lowest-performing students within the context of A.P. classes– that’s what regular college prep classes are for. The regular grade-level classes have time to focus on bringing students’ grades and skillsets up to standards, and helping them become proficient enough to move up to A.P. the next year if they so choose (and qualify academically). Receiving individualized attention at a more relaxed pace is miles better for some students than drowning in a sea of College Board-designed content that must be worked through at a fast pace to get it all done before May.

The idea of a prerequisite system is not unfair or discriminatory, as some may claim. Success in an A.P. class, or any class for that matter, is up to the student alone. Lincoln needs to expect more out of its students, and students need to earn their opportunities instead of just being handed them.

Rigorous A.P. courses should be limited to students who have proven in the past they are willing to work hard and who are academically prepared to succeed in a college-level classroom.